- Kodak: the biggest film company in the world loses business to fear

- Hummer: brawny status symbol turns into automotive pariah

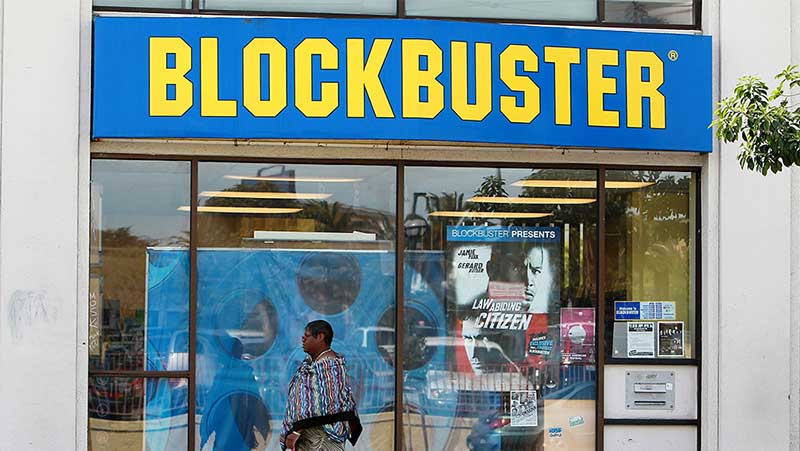

- Blockbuster: from iconic video rental brand to death at the hands of Netflix

- Polaroid: instant paper photos make way for digital slideshows

Many of the world’s former top companies have shrunk, floundered, become irrelevant, or been gobbled up by their rivals. In fact, almost 90 per cent of companies that were around and flourishing in 1955, for instance, have either perished, are forgotten, or are no longer major players. Resisting or ignoring the importance of innovation is one of the most effective ways to commit ‘business suicide’, and organisations need to be on top of their game more than ever to avoid falling by the wayside. Here’s a list of the most notable examples of companies that didn’t put innovation first – and paid the price.

Kodak: the biggest film company in the world loses business to fear

One of the most well-known examples is Kodak, the iconic brand that dominated the photographic film market for most of the 20th century. The company was founded in 1884 and invented roll film, which landed it fame and fortune. It became the biggest film company in the world. In 1975, the Kodak engineer Steve Sasson invented the first digital camera, but the company chose not to develop it because it was filmless photography. The company’s leadership was concerned it would be detrimental to its film business, and as a result, Kodak missed the digital revolution. Don Strickland, the former vice president of Kodak, says: “We developed the world’s first consumer digital camera but we could not get approval to launch or sell it because of fear of the effects on the film market.” Kodak filed for bankruptcy in 2012. “In my opinion, Kodak fell into the same trap that most large, successful and once highly innovative companies get into – how to keep the innovation engine working over the life of the company. Without a robust and resilient innovation strategy, no company can survive over the long-term”, says Phil McKinney, an author, host of the radio show Killer Innovations, and CEO of CableLabs.

Hummer: brawny status symbol turns into automotive pariah

The big, expensive, and tough Hummer, initially developed for the US military, became famous when Arnold Schwarzenegger bought the first civilian version of this powerful vehicle in 1992. It was a status symbol then, but these days, as consumers have become increasingly aware of the car’s detrimental effects on the environment, the Hummer is more synonymous with an expensive fuel guzzler, raising not only concerns, but eyebrows as well. With rising oil prices during the energy crises of the 2000s, sales of the largest SUV known to man plummeted and the brand shut down for good in 2010.

That same year, Nick Bunkley wrote for the New York Times: “Over the years, Hummer shifted from a brawny status symbol that drew attention on the road into an automotive pariah. Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger of California helped the brand become popular and once owned a fleet of Hummers, but more recently, he described the brand as prime evidence of the Detroit automakers’ failings”. Even the Chinese government blocked a takeover by Sichuan Tengzhong Heavy Industrial Machinery as the Hummer was “at odds with the country’s planning agency’s attempts to decrease pollution from Chinese manufacturers”, according to BBC News.

Blockbuster: from iconic video rental brand to death at the hands of Netflix

Founded in 1985, Blockbuster Video was one of the most iconic brands in the movie rental arena. In 2004, while at its peak, the company had over 9000 stores and employed close to 85,000 people worldwide. While it did survive the shift from VHS to DVD, it shied away from innovating into a market that was transitioning towards home delivery – and subsequently, streaming – of movies. It had been the market leader for many years and didn’t see the need to change its business strategy. It was convinced its physical rental stores accommodated its customers’ needs adequately. In 2000, Blockbuster was approached by Netflix to form a partnership. Netflix suggested that Blockbuster advertise the brand in its DVD stores, while Netflix would run Blockbuster online. Blockbuster found the idea ridiculous and turned down the offer. It saw Netflix as a struggling and “very small niche business”. The idea could’ve been Blockbuster’s saving grace, but instead – unable to transition towards a digital model – the company went bust in 2010. Netflix has since moved in and taken its market share, reaching 130 million subscribers at the end of July this year.

Polaroid: instant paper photos make way for digital slideshows

Polaroid was founded in 1937 and became one of the first US high-tech success stories in a market that knew few competitors. The company was best known for its instant cameras and film that produced photos that developed as you watched. Polaroid was at its peak in the late 1990’s when it employed 21,000 people. The company, however, filed for bankruptcy in 2001, following the emergence of digital photography. Polaroid’s leaders believed that paper photos were still what customers wanted. They failed to explore new territory and neglected to anticipate the impact of digital cameras on their film business. Their camera production was discontinued in 2007, while film production stopped in 2009. Andrea Nagy Smith writes for Yale Insights: “Through the 1990s, Polaroid executives continued to believe in the importance of the paper print. Gary DiCamillo, CEO from 1995 to 2001, said in a 2008 interview at Yale, ‘People were betting on hard copy and media that was going to be pick-up-able, visible, seeable, touchable, as a photograph would be’. When customers abandoned the print, Polaroid was taken by surprise. ‘It’s amazing, but kids today don’t want hard copy anymore,’ said DiCamillo. ‘This was the major mistake we all made: Mac Booth, Gary DiCamillo, people after me…. That was a major hypothesis that I believed in my marrow that was wrong’. Even though it performed thorough market research, Polaroid was unable to foresee that the photo album would be replaced by the digital slide show”.

Polaroid comeback

In 2017, a few former Polaroid employees returned to the old factory in Enschede, The Netherlands, which was closed by its American owner in 2008. They took over the machinery and started operating under the name Impossible, developing a new – but still analogue – camera. The camera is produced in China and is expected to bring about an instant-photography revival as analogue cameras are particularly popular among young people. The film-cassettes are produced at the head office in Enschede. The company, which is now once again operating under the Polaroid name, seems to be making a remarkable comeback. The worldwide demand for film cassettes for instant cameras – which are only produced by Fuji in Japan and Polaroid in Enschede – is exploding and the development time of the film packs is now only five minutes, instead of 15 minutes in 2009. The production figures for the film cassettes at the factory in Enschede are now 3.5 million a year, and to meet this demand, Polaroid Enschede is looking to expand its current workforce. A great deal of focus is also going into the further development of their One Step 2-camera.

The bottom line

The struggles of these brands are illustrative of how complicated it can be for leaders to change fixed mindsets, balance priorities, change processes, and focus on innovation. But organisations that don’t respond to changing markets or fail to acknowledge trends, invariably miss out on opportunities, risk losing their share of the market, and ultimately face their demise.

Share via: