- Nature provides amazing defenses for animals like the alligator gar and the conch.

- By studying how these armours work, scientists are making breakthroughs in materials science.

- New armour inspired by the alligator gar can protect first responders from needle sticks.

- The design of the conch shell may help scientists build a better helmet.

- Genetically modified silkworms now spin “Dragon Silk” for armoured underwear.

The law of nature is kill or be killed, and evolution has had a long time to perfect the claws, teeth, hide, and scales of its creations. From crocodiles to crabs, nature provides impressive defenses. Now, researchers, engineers, and scientists want to see what materials science can learn from studying biology.

They’ve good reasons to dig deep into nature’s bag of tricks. People need armour, too. From soldiers to policemen, waste handlers to butchers, many jobs involve the threat of slicing, cutting, stabbing, and poking. For instance, oyster shuckers wear a chain-mail glove on their hand to prevent accidents as they pry their knives between hard shells. And policemen often wear gloves to protect themselves from needle punctures as they search suspects. Of course, they don bullet- or knife-proof body armour, too, just as soldiers do. And let’s not forget the impressive armour worn by American footballers or hockey players, either!

But current designs leave a lot of room for improvement. They tend to be heavy, hot, and cumbersome, and though available gloves are good at protecting their wearers from cuts, they’re not great at stopping tiny medical needles. That’s clearly the larger threat. But with the help of engineering and biology, scientists may soon borrow nature’s tech to improve our own.

Gar skin gloves: protecting workers’ hands from needle sticks

Alligator gar are among the most ferocious fresh-water fish any angler can catch. They’ve got a mouth full of teeth, like an alligator, and their bodies are covered in a layer of tough, overlapping scales. It’s that natural armour that has caught the attention of Francois Barthelat, a mechanical engineer at McGill University.

These fish are so notoriously well-armoured that Barthelat was lured in by them. He’s studied other fish, but he’s never run into anything like the alligator gar. He and his team want to make protective gloves that are both flexible and impenetrable to needles, a truly tall order. To find out what resists a poke, they jabbed needles through a lot of flexible materials, looking for something that can stop a puncture but allow freedom of movement. When they tried to pass a needle through the alligator gar’s heavy armour, the needle just buckled. That got them thinking seriously about how those scales work.

Barthelat’s team soon realised that the shape, thickness, and placement of the scales mattered most, and repeated tests confirmed that the armour that best mimicked the alligator gar’s own system worked best. It turned out that smaller scales gave better protection, surprising the researchers. And what was great about this discovery was that it allowed them to adapt their design to gloves more easily.

In partnership with Superior Glove, Barthelat’s designing a layer of tiny ceramic scales that are added to a Kevlar base layer to enhance worker safety. Whether you’re a nurse, an EMT, or a waste worker, you’ll find yourself in environments where you need to handle contaminated needles. These new up-armoured gloves are passing every safety test, and you may soon see them on caregivers near you. “Nature has been finding solutions to ‘engineering problems’ over millions of years of evolution,” Barthelat explains. “For a long time biologists and engineers largely ignored each other, but this is now changing. Biologists are using more and more engineering tools and methods, and engineers are revisiting old engineering problems using bioinspiration. Biologists and engineers are now talking to each other more than ever before, which is very stimulating and makes [this] a very exciting time to be working in this field.”

American football might be saved by the humble conch

American football is having a closed-head injury crisis. Repeated impacts and un-noticed concussions are leaving these sportsmen with traumatic brain injuries that affect memory and lead to high rates of suicide. This has players and fans worried about the end of the sport. Markus Buehler, a materials scientist at MIT, has been rethinking armour from the perspective of nature, and like Barthelat, he’s come away feeling impressed. His discoveries just might save lives, and potentially save a sport Americans love.

If you’ve ever tried to crack the shell of a clam or conch, you know just how tough these natural defenses are. What’s amazing, however, is that they’re made from weak materials. As Buehler explains, the proteins and chalky minerals that a conch uses to make its shell are laughably awful on their own, basic “building blocks that engineers wouldn’t even touch”. But nature has found a way to enable this humble sea creature to make more from these poor materials than we ever thought possible.

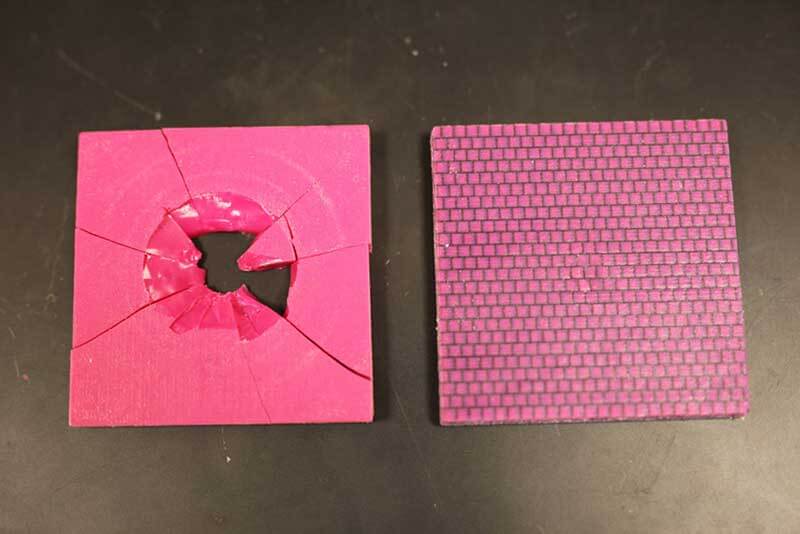

Buehler’s team wanted to know how, and they soon discovered that it was the way in which these materials were arranged that gave them their incredible strength. The conch shell sandwiches squishy Jell-O-like proteins between layers of hard calcium carbonate. The result is an amazing system that absorbs heavy impacts and protects the vulnerable snail inside. Using 3D printing, Buehler’s lab was able to produce a composite that increased the strength of armour by 85 per cent, allowing it to absorb crushing impacts without breaking.

And though his work is funded by the military, Buehler’s hopeful that this new material can be applied to bicycle helmets and other kinds of protective equipment used in sports, perhaps giving new life to American football. As Popular Science reports, current helmets are made from styrofoam and hard plastic, materials that simply can’t meet our high safety expectations. But this new nature-inspired material could allow helmets to become stronger while still being light-weight, allowing the game to go on.

Dragon Silk makes armoured underwear possible

You probably know how strong spider silk is; gram for gram, it’s much stronger than steel, but it’s also an incredible ten times stronger than the Kevlar we use in body armour. And unlike these synthetic polymers that don’t stretch very well, making body armour uncomfortable, to say the least, spider silk is incredibly elastic.

Scientists have known this for a while, but two obstacles slowed research. First, spiders don’t produce much silk. And second, the tiny cannibals can’t be kept together, making production a nightmare. Kraig Biocraft Laboratories found a solution. By genetically altering silk worms, adding the genes for spider silk to the tiny, living silk factories, they produced a miraculous new material. The result is that the worms, which live together easily and produce commercial quantities of silk, now make super-strong “Dragon Silk”.

The US military wants to incorporate this new material into body armour, but they’re also exploring the possibility of protective underwear. In their current combat environment, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) are a major threat. They explode from the ground up, defeating normal body armour and crippling soldiers. The hope is that Dragon Silk underwear could prevent injuries by stopping shrapnel, saving lives, and reducing injuries.

In each of these cases, scientists studied nature to find answers to their questions. If you think about it, evolution has been in a long-term arms race, answering one improvement with another. It only makes sense, then, that engineers and researchers turn to biology for clues about how to keep people safe.

Share via: