- The housing crisis shows no signs of improvement

- Rent a pod if you can’t afford an apartment

- Spherical mini homes in back gardens

- Is it a coffin or a living capsule?

- Affordable and popular modular homes in Ireland

- Cardboard houses and temporary neighbourhoods

- What will be the future of housing?

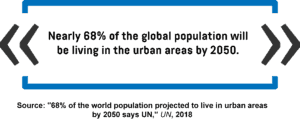

Each year, millions of people move to urban areas hoping to settle and find well-paid jobs. Migratory trends have made cities home to more than half of the world’s population, a proportion the UN expects to rise to 68 per cent by 2050. But as more and more people cram together, competition for scarce resources increases as well. The chronic lack of affordable housing options affects both developed and developing countries. In fact, residents from 26 out of the 28 European Union (EU) capitals say that it’s hard to find good housing at affordable prices, a problem that hits young people particularly hard.

Some real estate entrepreneurs, however, have recognised a business opportunity in the housing crisis. For instance, they’ve made it possible for people to rent beds instead of apartments in some of the world’s most expensive ZIP codes. Others build tiny capsules that draw strong criticism from local authorities, and tiny modular homes are increasingly popular as well. Some countries have even built entire temporary neighbourhoods that will be removed once larger and more affordable housing units are constructed.

The housing crisis shows no signs of improvement

Living in big cities is often a far cry from what people hope for. In the US, for instance, only a third of millennials currently own homes, while the same amount of young people in the UK might end up renting their entire life. In US cities that offer plenty of jobs, such as Los Angeles, rent for a two-bedroom apartment amounts to more than $2,000 a month, but salaries aren’t keeping pace with the housing market. And burdened by college debt, many Americans find it difficult to save money needed to buy their own house, or at least make a down payment to get a home loan.

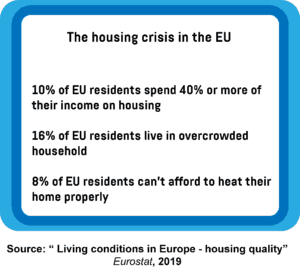

Many Europeans face similar challenges. Ten per cent of the EU population, which amounts to around 50 million people, are financially overburdened, as they spend 40 per cent or more of their disposable income on housing. This problem is more widespread among renters than homeowners. Furthermore, 16 per cent of EU residents live in overcrowded households, while eight per cent of people can’t afford to heat their home properly. And much like in the US, younger generations in Europe often face the biggest challenges in accessing affordable housing when they move to urban areas and start their careers.

Failing to tackle these issues can pose a major risk to economies, and the World Bank is urging policymakers to find a solution. Speeding up approval processes for new construction projects, allocating unused public land for housing development, and creating public registries to improve the transparency of house sale prices are some of the proposed solutions. But deploying these measures might take years, and time is a luxury that home-seekers don’t have, which is why companies that are providing cheap housing options are thriving.

Rent a pod if you can’t afford an apartment

One solution to the housing crisis is the co-living trend, and it’s been championed by startups such as PodShare. The company operates a number of buildings in multiple US cities, providing users with a single bed, private storage space, and lockers. The dorm-like facilities consist of a shared kitchen, bathrooms, living rooms, and a yard. Best of all, renters can stay at any PodShare location for a single monthly price, assuming there’s an available bed. Prices can vary slightly depending on the location, and in Los Angeles, for example, renting a single bed can cost around $1,400 a month. This might seem very expensive, but it’s significantly cheaper than renting an apartment in the same area.

Co-living spaces are also thriving in New York, Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco, attracting a diverse group of people. Jon Dishotsky, the CEO of a co-living startup called Starcity, says that there are four different types of customers. The first group are young people who are just starting their careers, and the second group are individuals in their 30s and 40s who possibly went through a divorce or left a bad roommate. Also, there are those who co-live because they believe in a nomadic and minimalistic lifestyle, and they form the backbone of the experience economy – a growing trend of consumers opting for experiential purchases such as trips and concerts instead of material items like jewellery or electronic gadgets. The last group of customers are those who need a place to stay for a month or two because of things like a job assignment.

Spherical mini homes in back gardens

Living in pods, as the beds in co-living spaces are called, isn’t tempting for everyone, however, as many people want privacy. Jag Virdie, a former Rolls-Royce engineer, might have an answer to their needs. He designed a spherical mini home called Conker that costs anywhere from $24,000 to $45,000, depending on add-ons such as a toilet, kitchenette, or wet room. It has around 10 m2 of floor area and requires no foundation, as it rests on four stilts. The object can be fitted with solar panels and has an efficient heat-retention system, making it a four-season housing solution.

The Conker is less expensive than traditional homes, and it can be customised with different colours on the outside and furniture styles on the inside. This dwelling can be installed in gardens within a day, providing those who still stay with their parents with a private living space. Besides this, Virdie says that the spherical home can also be “assembled or dismantled to function as, for instance, a temporary bar for shows, music festivals, and other events. There’s a lot that the Conker can do.”

Is it a coffin or a living capsule?

Not every housing solution developed by entrepreneurs is applauded, however, and some have met firm local opposition. The Barcelona-based company Haibu 4.0, for instance, wanted to construct pods that would be available to individuals that can’t afford to rent a typical apartment in the city of Barcelona. Each pod would have a bed, power plugs, a TV, and some storage space, while residents would share a bathroom and kitchen. The company planned to offer its services to people aged between 25 and 45, which earn a minimum salary of around $500 per month. The monthly rent would be $229, which would include water, electricity, and WiFi, and renters would enjoy more privacy than in hostels.

But local authorities weren’t too impressed, and some compared the 2.4 m2 capsules to coffins. The Barcelona City Council said that the project won’t get a certificate of habitability, as a one-person room must be at least five square metres in size. Nonetheless, Haibu 4.0 pushed forward with the construction, claiming that more than 500 people are interested in renting the capsules. The Council then took the case to the court, which ordered the police to seal the construction site. The company eventually sued the authorities, and it remains to be seen how the situation will unfold.

Affordable and popular modular homes in Ireland

Unlike Haibu 4.0, the Ireland-based Pod Factory can hardly keep up with its booming business. The company produces 22 m2 modular homes that cost around $50,000 and have a thirty-year lifespan. It takes six to eight weeks to produce and deliver a house to customers, with the Pod Factory also connecting utilities such as water, electricity, and gas. This tiny home comes with a fully equipped kitchen, bathroom, living room, and bedroom. What’s more, these ‘pods’ can also be stacked to form two-storey homes, if needed.

Typical customers include expats that are planning to return to their homeland, young couples that are looking for affordable housing, and older people that want to downsize and live in smaller houses.

Cardboard houses and temporary neighbourhoods

The Netherlands-based firm Fiction Factory also constructs prefab houses, called the Wikkelhouse. Led by Oep Schilling, the company uses cardboard as the main structural element to produce 5 m2 modules that customers put together to create house-shaped structures of any size they want. A module of 50 square metres costs up to $78,000, depending on layout options, and it takes one to two days to install. It’s fully recyclable and three times more ecological than typical houses, with a lifecycle of at least 50 years. Also, since one module weighs only around 500 kilograms, the Wikkelhouse requires no concrete foundation and can be placed at almost any location.

Another Dutch solution to the housing crisis can be found in Rotterdam, the country’s second largest city. Authorities have approved the construction of up to 3,000 mobile prefabricated houses that will serve as a temporary housing solution for low-income residents. The plan is to essentially buy some time and provide people with a roof over their head until more permanent and affordable homes are constructed. The city of Nijkerk has already completed the construction of 28 temporary homes known as ‘tiny houses’ in September, 2018. These 39 m2 households are arranged into clusters of four. The monthly rent costs $465, and renters are expected to spend up to two years in these homes until they find a more permanent solution. And in each cluster of homes, one unit is reserved for a low-income young person, one is for a person with a recognised asylum status, and two units are for people with emergency housing needs.

What will be the future of housing?

The lack of affordable homes and massive migration to cities worsens the already rampant housing crisis. Many people hardly have money to rent an average apartment, let alone buy a house. And while authorities are aware of the scale of this issue, there are no quick fixes, and any solution will take years to produce successful results.

Such gridlock led to construction industry experts developing various concepts such as tiny houses and pods. But whether providing people with ever smaller living spaces is a solution to the housing crisis and homelessness remains an open question. Sure, flexible and minimalistic housing suits travellers, digital nomads, and people with urgent housing needs. But while businesses provide a short-term remedy to the housing crisis, it’s up to policymakers to find long-term solutions and ensure that owning a home becomes less of a dream and more of a reality for millions of people worldwide.

Share via: