- Social isolation and confinement can lead to a variety of mental health issues

- NASA is simulating Mars-like conditions on Earth

- Other stress management techniques include virtual reality simulators and automated computer programs for depression

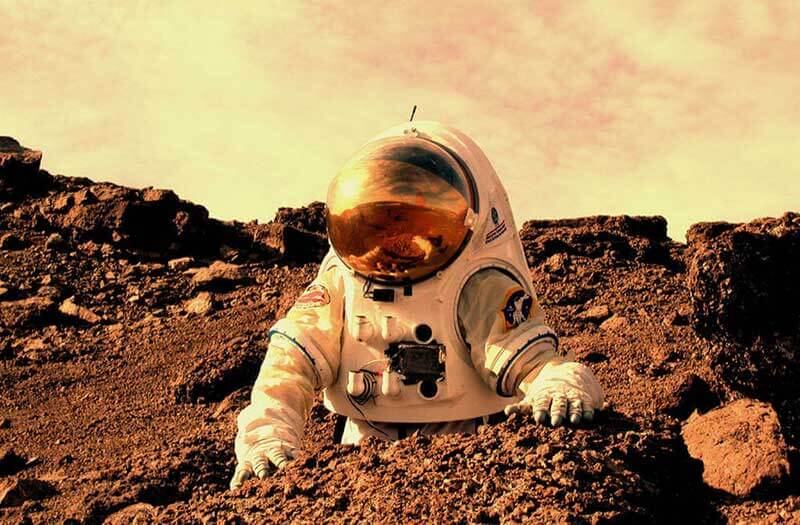

Going to Mars has long been humanity’s dream, but until recently, the whole idea was nothing more than a popular plot for science fiction authors. That’s changed. Thanks to the latest technological breakthroughs, we are now finally ready to take the next step in space exploration and send people to the Red Planet. In fact, there are already several projects in the works, including Mars One, a private one-way trip to Mars planned for 2022, as well as NASA’s own manned mission to Mars, which is scheduled for sometime in the 2030s. The only question left to answer is: how do we make sure our people will be safe once they get there?

There are numerous dangers awaiting astronauts in space, from meteorites and radiation from solar flares to the effects of lower gravity on their cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems. But the biggest danger may actually be to their mental health. Social isolation, confinement, loss of privacy, and the lack of mental health services are just some of the factors astronauts will have to learn to cope with to thrive on Mars.

Social isolation and confinement can lead to a variety of mental health issues

Social isolation is one of the biggest issues associated with space travel. It takes up to 45 minutes for radio waves to travel between Mars and Earth, and that means that the astronauts won’t have the ability to communicate with friends and family back home in real time. Worse still, they’ll be cooped-up with their fellow explorers, spending months if not years in close quarters. In such conditions, even the smallest detail can become unbearable given enough time. “When you’re stuck with people over these long durations, micro-stimuli can become really irritating,” says Kim Binsted, a University of Hawaii psychologist who studies the effects of human spaceflight. “Let’s say you can’t stand the way your crew-mate chews his cereal. Suddenly it goes from ‘Eh, I wish he’d close his mouth more’ to ‘I’m going to stab him.’” And it’s not like you can just go outside for a walk to calm your nerves. According to research, prolonged isolation can lead to a variety of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, fatigue, boredom, insomnia, and emotional instability. And even the most highly trained astronauts are not immune to these effects.

Then, there is also the matter of confinement. With an unbreathable atmosphere and average temperatures of around -60 degrees Celsius, the astronauts will have to spend the majority of their time inside in remarkably small spaces. For example, NASA’s current Mars Transit habitat concept, which is supposed to hold four astronauts and their gear, is only 8.5 metres high, 8.5 metres wide, and 5 metres long. The participants in the Mars One project will be in a similar predicament, with just 50 square metres allocated per person. And prolonged confinement in small spaces can produce similar symptoms to social isolation, such as anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment.

NASA is simulating Mars-like conditions on Earth

How can we make sure that the people we send up there won’t lose their minds? Considering that nobody has ever gone to Mars, our best bet is to try to simulate the conditions as faithfully as possible here on Earth and see how people react. For this purpose, NASA built a 110-square-metre analog habitat called the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation, or HI-SEAS. Located in an isolated area on the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii, HI-SEAS allows researchers to place volunteers in a Mars-like environment for up to a year and study how they respond to things like extreme isolation and time-delayed communications.

Previously, NASA used the Human Exploration Research Analog (HERA) to run 45-day isolation tests on their crew. However, according to Binsted, that’s not enough time to properly conduct that kind of study, because it usually takes about six months for the stressors to come out. Five HI-SEAS simulations have been successfully completed so far and the biggest takeaway is that every crew will start fighting eventually, regardless of the group dynamics. But there are also ways to increase the likelihood of mission success, including making sure that the crew members are compatible with one other.

Mars 500 was a psychosocial isolation experiment conducted between 2007 and 2011 in Russia by the Russian Federation, European Space Agency, and China National Space Administration, in which six male volunteers were placed in simulated spacecraft for 520 days. During that time, the volunteers were given weekly questionnaires asking them to assess their mood, stress, depression levels, fatigue, reaction time, and conflicts with others. What they discovered was that crew members had varied responses to stressors, with one man showing some symptoms of depression in more than 90 per cent of the mission weeks, while two others showed no signs of psychological distress or behavioral disturbances throughout the simulation.

Other stress management techniques include virtual reality simulators and automated computer programs for depression

NASA is also trying to develop systems that will be able to monitor the astronauts’ brain activity, heart rate, and cortisol levels in their bloodstream, elevated levels of which have been linked with higher risk of depression and mental illness. The problem with invasive monitoring is that it could potentially put additional stress on the astronauts, so NASA is looking at something more subtle, such as AI systems capable of reading astronauts’ facial expression and their language, or sociometric badges that could detect angry voices and notify the crew commander. Furthermore, NASA is also exploring other techniques that could help astronauts cope with anxiety and depression, such as virtual reality simulators and interactive computer games. For instance, Deprexis is an automated computer programme for cognitive behavioral therapy that has been shown to deliver small to moderate benefits in depression. Even though it’s only half as effective as normal psychotherapy, it can certainly come in handy in conditions where real time access to counselling and psychotherapy isn’t possible.

With a manned mission to Mars a virtual certainty in the near future, the race is on to ensure that everything runs smoothly and that the people we send up there are safe. In addition to various physical dangers, space exploration presents a known risk to astronauts’ mental health. Social isolation and confinement in particular can lead to a variety of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, insomnia, fatigue, and cognitive impairment. NASA is doing everything in its power to prepare its crew for a prolonged exposure to these stressors, including simulating similar conditions here on Earth. However, the truth is that we won’t know for sure what will happen until they actually go out there.

Share via: