- Hyper-reality – a step beyond the virtual

- Big business advertises it as entertainment

- Others see it as a dark vision of the future

You’re probably familiar with augmented reality wearables. They provide a graphical overlay superimposed on the real. You don’t just see what’s there, you see what’s there plus digital content. You might know someone who owns Google Glass or have seen the craze around Pokémon Go, early examples of this new and evolving tech. But the future of this tech is mind boggling. It’s hyper-real, a leap beyond the merely augmented.

One step beyond the virtual

Imagine teachers leading students through a museum as they interact with graphic overlays and information about the exhibits. Or foremen who wear helmets that display critical information about the building they’re constructing and allows them manipulate drones and robotic workers. Or surgeons who wear a visor that lets them see your internal injuries. Soon, such augmented wearables will be everywhere. But they’re not all work and no play.

Hyper-real, immersive entertainment

You’ve probably imagined yourself as the hero or heroine of your favourite action or adventure film. Who hasn’t? That’s part of what makes movies popular: immersion, wish-fulfilment, and the chance to lose yourself in a story for a few hours. But this new technology is promising a lot more than that. You can now take a leap beyond film—seeing, hearing, touching, and smelling a virtual world so real that you are warned to reach out and touch a wall if you become disoriented. Think about that for a moment— a virtual experience so immersive that you need to be reminded that all the walls are real— really real. That gives you a good sense of just how powerful this experience is: it’s impossible to tell fact from fantasy, real from virtual. This is the new hyper-reality.

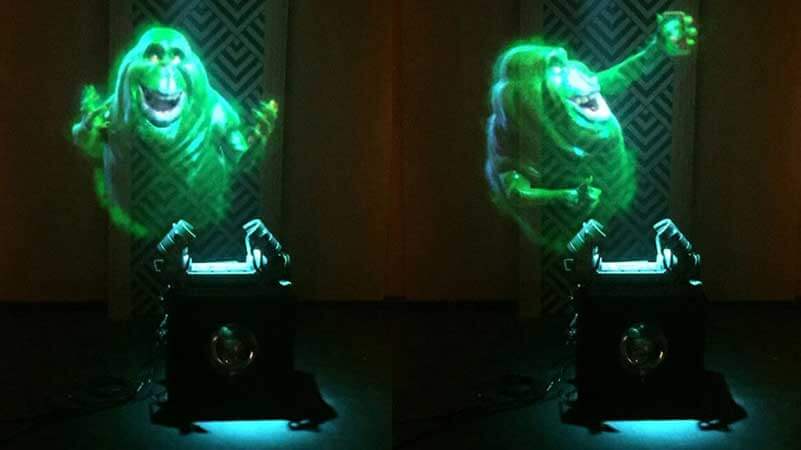

The VOID and Ghostbusters

The brainchild of Ken Bretschneider, Curtis Hickman, and James Jensen, who founded Visions of Infinite Dimensions in 2014, the VOID offers its users the chance to experience the excitement of movies, in this case the Ghostbusters franchise, in a way that could only be dreamt of before. It’s perfectly appropriate that this artistic trio has set up shop in collaboration with Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum in New York City. Wax figures that are indistinguishable from real people was the old tech; augmented reality so vivid that it breaks our sense of the real is the new.

The VOID shares Tussaud’s artistic magic, but unites it with high-tech wizardry. Tracking users with motion capturing software, this augmented reality offers a seamless experience of the set pieces familiar to moviegoers. By mapping every virtual object with a correspondingly real thing in ‘meatspace,’ a virtual world is brought to life. When you reach for a virtual object, your hand finds something tangible. Users describe a complex of overlaid effects that trick the mind; you know it’s not real, but you experience it as real anyway. You feel the texture of wood panelling in a hotel you know isn’t there, get hit with wet when you’re slimed by protoplasm, and smell roasting marshmallow when you cross streams to defeat the Stay-Puft marshmallow man. Your senses don’t lie to you, so there’s no effort to maintain the illusion. It’s make-believe without imagination.

Hyper reality as social experience

Hyper reality as entertainment offers an interactive, virtual experience that requires no suspension of belief. You could be anyone, anywhere, anytime. According to early reports, an unexpectedly critical part of the immersion is the interaction of you and your fellows—and at present, the avatars you see are all male, unfortunately. Caught up in this real make-believe, you find yourself bonding with strangers in a way that creates surprising emotional depth.

It’s this social component—this resonant experience of playing together—that has Silicon Valley exploring the limits of VR. They’re not looking for a movie you watch, not even a movie you play in, but a movie you play in with others. The possibilities are really exciting. After all, what we’re really talking about is very close to the Matrix. But as you might expect, this blurring of the line between fact and fiction has some people worried.

Hyper reality and the gamification of life

While big business sees big profits, this Matrix as a Morpheus of its own, and he sees a dangerous dream of humans powering a future in which they are the unwilling slaves of machines. And he wants to wake you up before the nightmare begins.

His name is Keiichi Matsuda. He crowd funded a six-minute video offering a far less utopian vision of hyper-reality. He wants people watching his short film to see a less sunny—less pre-packaged–vision of the future of products like Google Glass.

Something, he says, to counter the slick commercialism of Silicon Valley. Something that reflects our real-world frustrations with social media, ads, and everything high-tech. Instead of an interactive movie, imagine no separation between the physical and the virtual, no space between consciousness and media. No way to tune out, to concentrate, to avoid a relentless barrage of digital interruptions. It’s not the possibilities for entertainment that worry Matsuda, it’s the intrusion of media overwriting the real.

Matsuda’s short film finds us behind the eyes of Juliana Restrepo, an underemployed woman in Medellin, Colombia. Restrepo is caught in a deep technical-existential question. ‘Who am I?’ she Googles in mid-air. ‘Where am I going?’

As Matsuda shows us, the answer is complex.

A slick yet dull future

For six minutes, we see through Restrepo’s eyes her life in the future, but it’s really our lives we’re watching. The journey to nowhere begins on a bus while she plays a typical time-wasting game. As she plays, we’re bombarded with advertisements and stunned by colours and sounds. It’s like the most annoying game you’ve very played crossed with the most irritating news channel graphics you can imagine. Only on steroids, extreme, and maximum strength.

Restrepo’s distraction is soon interrupted by a call from a digital ‘job guru’ who’s tracking her work progress. He urges her to work faster, but even as he does, it’s clear that everything has become a game. Every aspect of life is gamified in this dystopian future, and Restrepo is losing points fast. She is behind schedule, and frustrated.

“Have you tried running? It’s healthy and efficient!” says the guru.

We soon discover that she works as a personal grocery shopper, even though she studied to be a teacher. What Matsuda doesn’t need to tell us, is that this hyper-connected future doesn’t require many flesh and blood people to do the work that needs doing. Data on her task progress floats to one side and new, menial jobs are displayed on the other. There’s nothing of interest there; no real possibility. All the energy in the scene is virtual.

“Trust the app, it always chooses the right jobs for you!”

Restrepo doubts that. We do, too.

We share her listlessness as we watch the job guru comfort her with the empty praise. Insult is added to injury as he tries to entice her with the promise of loyalty points earned while shopping. And she’s obviously not convinced, but rather forced through the paces of this dull life by the threat of losing points—points that pay for everything from coffee to rent. This game has real consequences. She’s a slave to an app, little more than a biological piece in a silicone puzzle.

We watch as she resigns herself to the slick emptiness of constant media. From behind her eyes, impossibly busy visuals blind us and a constant barrage of pings and rings deafens us to the world. On the street, we are warned with busy red lines to avoid oncoming traffic, a real risk given the omnipresent distractions. To help us find our way through the electronic noise, we’re offered a marked pedestrian path of calming blue behind the flashing visuals fighting for our attention.

Each person we pass is a clearly advertised social media opportunity. We go shopping with her, and are distracted by the product placements, ads, and gimmicks familiar enough that we already hate them. They’re like the ones that plague us now. Only they’re more in your face. More present. More real. Hyper-real.

And we begin to see Matsuda’s vision from within this cyber stream-of-consciousness: hyper-reality is a trap, an existential dead-end. A future in which people are merely a resource to be exploited by a world run by Starbucks and Facebook. Until a glitch brings it all crashing down and we have a merciful moment of reality. Just plain reality. Like a glass of water after some too-sweet ice cream. In these blissful few seconds, her wearable is shut down. It’s been hacked, and to ‘save’ the points she’s earned at work, she needs to force a hard restart. We watch the world of Day-Glo colours fade to the greys and blues and greens of normal life in the frozen food isle of a grocery store.

The only distraction then is a crying baby. A sound that’s usually ear-splitting takes on a different tone entirely in the sudden absence of electronic noise. The crying is natural, unadulteratedly human. It’s somehow comforting—a lone reminder of the reality behind the augmented and virtual. And that’s Matsuda’s point.

The danger of the hyper real is that we lose our place in it, that we allow it to consume life and give us something slicker, cheaper, and less real in its place. Instead of a movie in which we play interactive parts, Matsuda sees the future as a constant, inescapable commercial.

And that just might be something to be scared of.

Share via: