- Orbital debris poses a significant threat to the ISS, satellites, and spacecraft

- The amount of space junk has increased so much that we’re at the tipping point

- A new satellite platform designed to capture space junk could be a solution

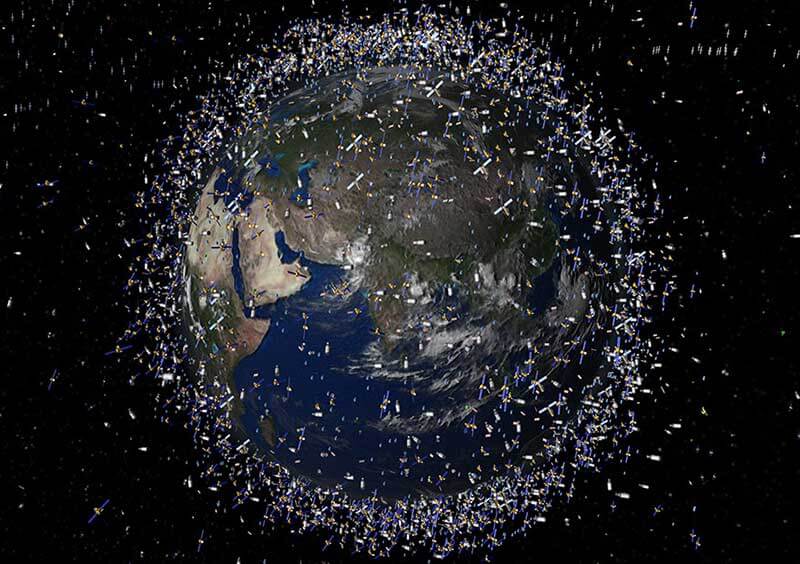

Apparently, polluting the Earth’s air, water, and land just wasn’t enough for humanity; we had to leave our mark on space as well. Over the last couple of decades, the Earth’s orbit became littered with defunct satellites, derelict spacecraft, spent rocket parts, and countless other pieces of man-made junk. According to NASA, there are now more than 21,000 pieces of debris larger than 10 centimetres floating around in orbit, over 500,000 pieces between 1 and 10 centimetres in diameter, and more than 100 million particles smaller than 1 centimetre.

Orbital debris poses a significant threat to the ISS, satellites, and spacecraft

While these pieces don’t pose any significant threat to people on Earth, because most of them would simply burn up in the atmosphere on re-entry, they could potentially be extremely dangerous for people and objects up in space. Travelling at speeds of up to 8 kilometres per second, even the tiniest piece of debris could cause major damage if it collided with our functional satellites, the International Space Station, space shuttles, or any other type of spacecraft. “A one centimetre object can have an energy on collision that is comparable to an exploding hand grenade,” says Tim Flohrer, a space debris expert at the European Space Agency.

The amount of space junk has increased so much that we’re at the tipping point

The cost of launching objects into space has decreased significantly in recent years, resulting in an exponential increase in the number of space ventures. As the number of objects in space grows, so does the amount of orbital debris, which could also endanger future missions to the moon and Mars, hinder the operation of our existing satellites, or even entirely prevent us from launching new satellites into space. “We’re at the tipping point,” says John Crassidis, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University at Buffalo. “If we don’t do something, it’s not going to be that much longer before there’s so much space junk and the probability of a collision is so great that nobody is going to want to insure satellites anymore.”

This tipping point even has a name – the Kessler Syndrome. Coined by the retired NASA scientist Donald Kessler in 1978, the term describes a worst-case scenario in which the amount of space junk reaches a point when it launches an unstoppable chain reaction of collisions that exponentially increases the amount of orbital debris and renders low-Earth orbit completely unusable. So, what do we do? Restricting the number of objects we send to space won’t be enough, because it will just delay the inevitable. The only way to prevent this development is to remove some of the larger pieces of debris from space. Thankfully, there may be a way to do it.

A new satellite platform designed to capture space junk could be a solution

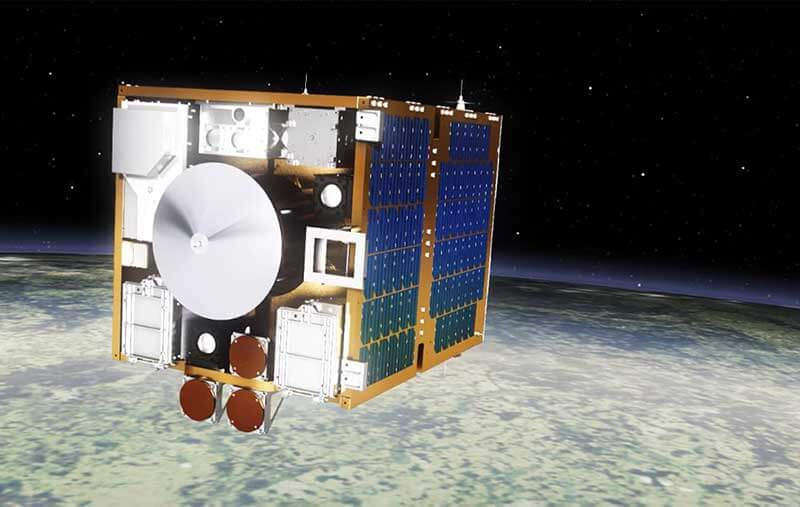

A consortium of universities and aerospace companies led by the Surrey Space Centre at the University of Surrey, recently performed a successful test of a high-tech satellite platform designed to capture space junk. The RemoveDEBRIS platform was launched to the International Space Station using a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and then deployed into orbit. Once in orbit, the platform initiated the first in a series of experiments by ejecting a tiny standardised satellite known as a CubeSat, which then proceeded to inflate a balloon to increase its size and provide a larger target area. When the CubeSat was 7 metres away, the platform ejected a net that successfully wrapped around the target, which was then left to de-orbit and burn up in the atmosphere.

However, according to Guglielmo Aglietti, the director of the Surrey Space Centre, the actual debris-removal mission would be slightly different from the test, because the net would remain tethered to the RemoveDEBRIS platform throughout, reeled in, and then de-orbited. The platform would mainly focus on removing larger pieces of orbital debris, because they represent the biggest threat to the ISS and our functional satellites. “If they collide with other things, they can explode and break into thousands of fragments,” explains Aglietti. “Rather than trying to remove smaller bits, which would be technologically very challenging, we think the best thing is to remove large pieces — especially those in busy orbits.”

The next experiments will involve testing a tethered harpoon that uses a flip-out locking mechanism to latch onto a piece of orbital debris and removes it from orbit, as well as testing a dragsail that will take the satellite out of orbit quicker and allow it to burn up faster in the Earth’s atmosphere. “We thought technologies like the harpoon or net are relatively low-cost,” adds Aglietti. “If we can demonstrate technologies that are affordable, there’s a much higher probability this will happen.”

The amount of space junk in Earth’s orbit has increased exponentially in recent years and now poses a significant threat to the International Space Station, our functional satellites, and any spacecraft that carry human passengers. If the current trend continues, we’re soon going to reach the tipping point known as the Kessler Syndrome, when the amount of space junk will increase so much that it will render low-Earth orbit unusable. The only way to prevent this from happening is to remove larger pieces of debris from space before it’s too late. As demonstrated by the scientists from the Surrey Space Centre, we may already have the technology to do it, but we need to act soon. If we don’t, the consequences will be huge.

Share via: