- Social media is fuelling the spread of fake news

- The rise of deep fakes

- A looming threat to individuals and businesses

- Democracy and facts under siege

- Solving the problem is harder than we thought

- Tech companies are fighting back

- Just how far is far enough?

Fake news took the world by storm in the last few years, and it’s blamed for worsening existing political and social problems, and even creating new ones. The French Secretary of State for Digital Affairs, Mounir Mahjoubi, for instance, recently accused the Yellow Jackets protest movement of spreading disinformation and fake news. Across the Atlantic, over half of US citizens claim to regularly see fake news on social media. And the influence of this phenomenon isn’t dwindling down. In fact, it recently took a turn for the worse, as deep fakes, which are fabricated videos of people saying or doing things they never did or said, have become more sophisticated.

From realistic and yet fake speeches of the US President Donald Trump to made-up sex tapes featuring celebrities like Gal Gadot, we’re witnessing an emergence of a dangerous trend. Artificial intelligence-powered video and image manipulation is becoming a new weapon used to blackmail individuals, cause mass panic, and even undermine public trust in democracy.

Social media is fuelling the spread of fake news

Facebook remains a key platform for distributing fake news, and the top 50 fake stories of 2018 generated around 22 million total shares, reactions, and comments.

For instance, fake news titled “Michael Jordan Resigns From The Board at Nike-Takes ‘Air Jordans’ With Him” generated 911,336 engagements. It was published shortly after Nike announced that Colin Kaepernick, a former NFL quarterback, would be the face of its new marketing campaign. He’s well-known for his activism and kneeling during the playing of the US national anthem prior to games as a way to protest racial injustice in the country, which prompted the outrage that ‘gave birth’ to this fake news. Michael Jordan, however, was never even a member of Nike’s board of directors, and hence couldn’t resign from it.

But fake news about athletes doesn’t have as much impact as when high-ranking politicians are involved. In 2016, for instance, BuzzFeed News reported that the top-performing fake news story involved former US President Barack Obama, claiming that he “had banned reciting the Pledge of Allegiance in schools”. This fake news was published on ABCNews.com.co, which is a fake website with a URL made to resemble the ‘real deal’ – ABC News – making this article even more potent. In fact, this fake news article generated more than 2.1 million comments, shares, and reactions on Facebook in just two months, and the story had been viewed more than 110,000 times.

Facebook explains that it might miss fake news pieces like these for several reasons. For instance, it can simply fail to identify fake articles (because they often look like any other news article), or identify them only after they’ve already gone viral. And even when fake news is caught early, it might still go viral in the time it takes for fact-checkers to actually prove it’s fabricated. This imperfect system explains why social media in general has become a breeding ground for information warfare.

But with deep fakes looming on the horizon, we’re in for very realistic fabricated content that could, in the future, fool even credible news sources, prompting them to publish it. Compared to fake news, deep fakes could have far more devastating consequences.

The rise of deep fakes

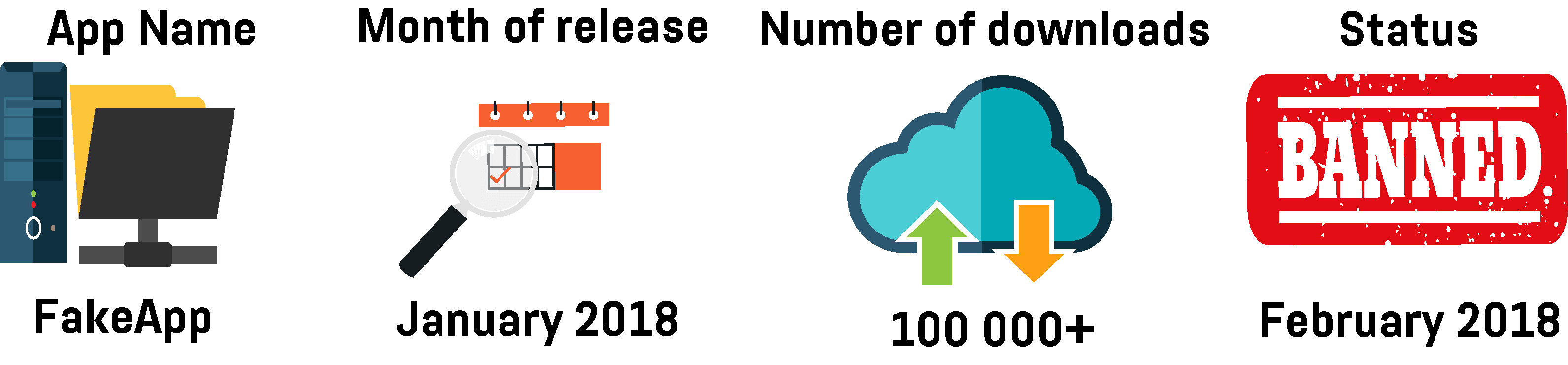

Deep fakes first appeared on Reddit in late 2017 in the form of fake porn videos of several female celebrities. This technology was soon made available to the general public, as in January 2018, a desktop app called FakeApp was released. The app allows users to create realistic videos with people’s faces swapped, and it was downloaded more than 100,000 times before Reddit banned it a month later. But this software tool, powered by deep learning algorithms and facial-mapping software, had already spread across the internet and people started to create an ever-growing number of fake videos that were gaining traction online.

Researchers at the University of Warwick conclude that false rumours spread more widely online than the truth, and they usually take more than 14 hours to be exposed. With these facts in mind, it’s clear why made-up videos spread so fast.The virality of videos created by FakeApp and other similar tools like Face2Face, which enables the user to create deep fakes in real time and put words in the speaker’s mouth, brings us a step closer to potentially catastrophic scenarios.

And we might soon face another trend, as researchers from Heidelberg University in Germany tested deep fakes technology that can manipulate not only someone’s face but even their entire body. The tech is still far from perfect, though, and it can be easily noticed that the videos are altered. But once fully developed, this technology could offer frightening prospects, especially when combined with technologies that enable voice imitation and lip synchronisation. Researchers at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in the US, for instance, managed to impersonate other people’s voices and even trick biometric authentication systems. A sign of things to come is also the recent highly sophisticated deep fake video, in which the face of Steve Buscemi was superimposed onto Jennifer Lawrence as she was speaking at the Golden Globes.

A looming threat to individuals and businesses

Deep fakes can be weaponised against individuals in devastating ways. They can destroy years of hard work, tear families apart, and inflict crippling reputational harm. What’s worse, this is already happening. Rana Ayyub, an investigative journalist in India, was a victim of deep fake porn that was, as she explains, intended to discredit her “through misogyny and character assassination”. Ayyub was harassed online, her privacy was invaded, and she had to close her Facebook account. In the end, only pressure from the United Nations forced the government to intervene and protect her.

Besides political actors, hackers are another group that’s bound to exploit the virality of deep fakes. They could insert malware into video files to gain access to a computer and steal valuable data like credit card details or passwords for online sites. If the computer is part of a company’s network, this could potentially jeopardise the security of the entire firm. Blackmailing executives and large companies, however, is perhaps one of the most financially destructive uses of deep fakes.

Made-up videos of CEOs engaged in compromising activities or saying racist comments might plummet the stock prices of a company overnight, causing major damage. Michelle Drolet, the founder of the data security company Towerwall, argues that executives blackmailed by deep fakes might see paying up as the less damaging course of action than claiming that the video is fake. And there’s no lack of people that are ready to use blackmail to get what they want. In England and Wales alone, for instance, the police recorded 8,333 blackmail offences in the 2017/18 period, and this trend just keeps growing.

Democracy and facts under siege

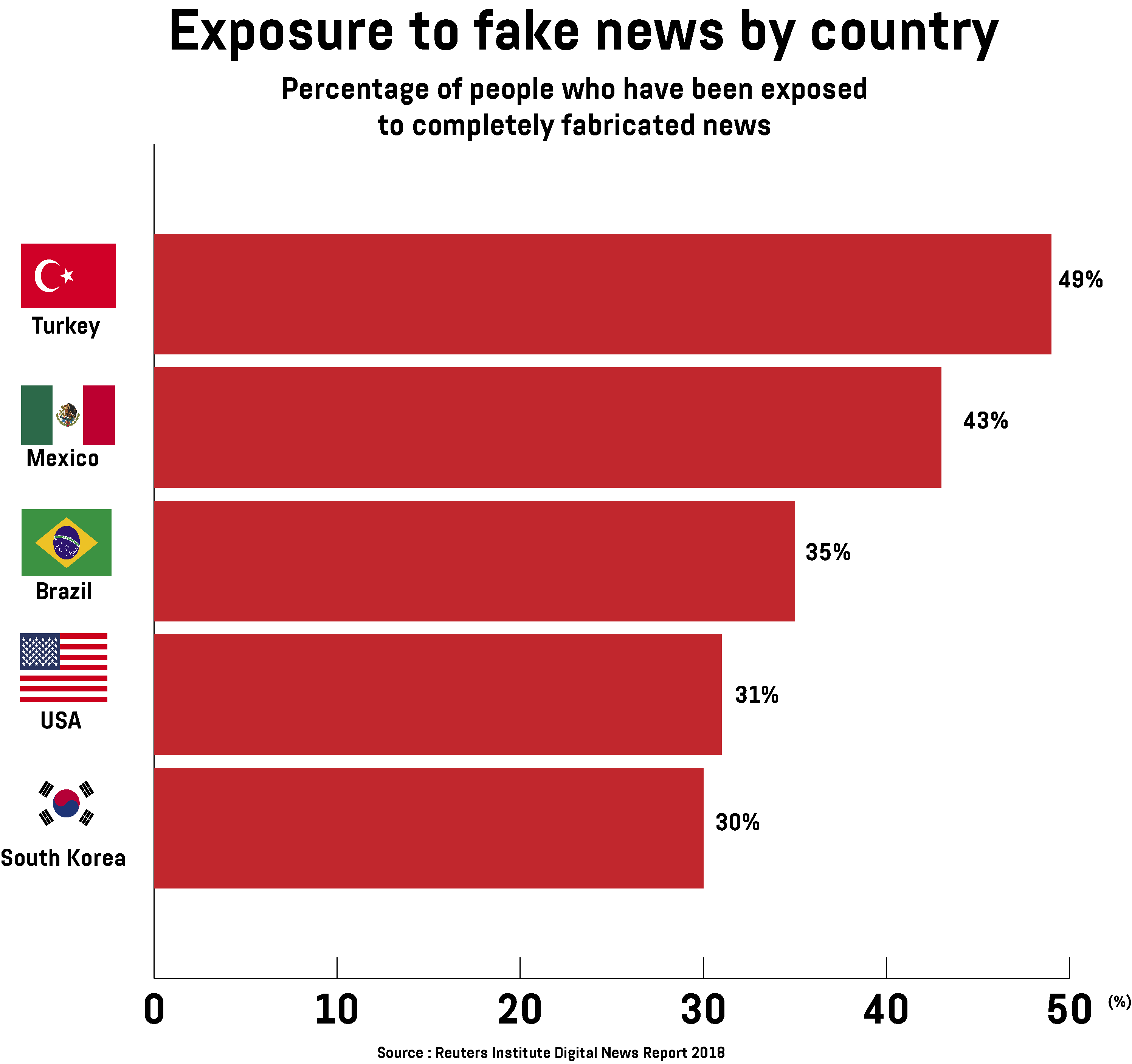

All of this, nevertheless, fades in comparison with the unsettling potential of deep fakes to undermine political and governance systems in democratic states. The terrain is already set, as in countries like Turkey and Mexico, more than 40 per cent of people believe they’ve been exposed to fake news, while in Brazil, South Korea, and the US, that number stands at 30 per cent or more.

With this in mind, imagine the negative effects of a video that portrays the country’s president taking bribes on the eve of the election. Another terrifying possibility, as law experts Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron argue, is that a fake video might depict officials announcing an “impending missile strike on Los Angeles or an emergent pandemic in New York”. To demonstrate what the future might hold, the actor and producer Jordan Peele teamed up with BuzzFeed and created a deep fake video of the former US president Barack Obama expressing a profanity-laced opinion on Donald Trump.

Solving the problem is harder than we thought

Lawmakers in the US seem, at least for now, most rattled by the danger posed by these new technologies, and they’ve sounded an alarm. The U.S. Senator Marco Rubio, for instance, called deep fakes a national security threat, and members of Congress sent a letter to Daniel Coats, the director of National Intelligence that serves as the head of the US Intelligence Community, asking him to step up the fight against the new threat. Senator Ben Sasse even introduced a bill proposing up to ten years of prison for the creators of deep fakes that might disrupt the government or incite violence. What’s more, social media platforms might get punished if they knowingly distribute deep fakes.

But solving this problem is a lot more complicated than writing a new bill. Social media companies might start taking down even genuine content in fear of penalties, while strict laws might criminalise harmless parody videos, curbing free speech. And since many of the potential attackers that could create and distribute deep fakes reside outside the US, they wouldn’t be deterred by strict sanctions. These issues notwithstanding, authorities in both the EU and the US expect Facebook and other social media giants to step up their fight against fake news and deep fakes. Mariya Gabriel, the European Commissioner for digital economy and society, says that “the time for fine words is over” and that internet companies must do a better job at fighting fake news and propaganda campaigns.

Tech companies are fighting back

However, there are no quick fixes to this problem, and the most likely scenario would be tackling deep fakes through incremental steps. Informing people about untrustworthy sites, like Microsoft’s Edge browser does, is a good start, while the next step might be researching the phenomenon and creating new tools. For instance, Vijay Thaware and Niranjan Agnihotri, researchers at the cybersecurity company Symantec, have developed deep fakes-spotting software by training AI with 26 deep fakes and accounting for the fact that people in fabricated videos don’t blink often enough. They claim the software is promising, but didn’t disclose the precise success rate, and they note that it works only on videos that are longer than a minute and aren’t fully artificially generated nor highly sophisticated.

Tech consultants like Akash Takyar suggest turning to blockchain and creating a news platform based on this technology. For instance, tracking the news source by assigning a unique QR code to each article or video is one way to do it. The Decentralized News Network came the closest to implementing this approach, but its token-based reader funding model leaves a lot to be desired, as in the era of free news, only the most well-known media companies can make readers actually pay to read their articles.

Truepic is another blockchain startup with tech that could be used to tackle deep fakes. The company has developed a smartphone camera app that verifies the integrity of an image by checking, for instance, that the camera’s coordinates and time zone are in line with those of surrounding Wi-Fi networks. In other words, it confirms that the photo was taken where and when the author says it was. After that, the image or video is stored onto a blockchain network, and if it ever goes viral, it can always be compared against the original. Truepic plans to work with mobile producers to make its tech an industry standard, and in that scenario, only pictures that match with those in the company’s blockchain database could get a ‘check-mark’ on social media, ensuring they’re not fake.

Just how far is far enough?

We believe that astronauts set foot on the moon in 1969 and that a man bravely stood in front of tanks at Tiananmen Square in 1989 because of irrefutable video proof. But advances in technology and the creation of AI-powered deep fakes threaten to change our trust in audio and video forever. Fighting this menace, however, is a complex undertaking that requires coordinated efforts from tech companies, governments, and citizens.

Will artificial intelligence or blockchain prevail over deep fakes? Are private companies better at handling the challenge than public institutions like the Pentagon? There are no definite answers, but what’s sure is that the future looks even more terrifying, as full-body deep fakes increasingly appear to be the next stage of the problem. Technology can be used as a force for good, but it can also serve nefarious goals, and one can’t help but wonder whether humans are engineering their own downfall.

Share via: