- Biased big data leads to biased decisions

- Can AI reduce court backlog and speed up trials?

- AI helps people save money on legal fees

- A chatbot instructs users how to “sue anyone”

- Defining our approach to the automation of justice

To say that legal systems in many countries around the world are inefficient would be an understatement. Overcrowded prisons, backlogged courts, and overburdened public defenders are just some of the many pressing issues currently facing the legal field. For instance, courts in Germany can take up to two years to decide on asylum applications, while, with around 2.3 million people in jail, the US imprisons more people per capita than any other country in the world. What’s more, around 540,000 of these incarcerated individuals aren’t even convicted or sentenced yet. The situation in Europe is slightly better. According to a recent report by the Council of Europe, the overall imprisonment rate in Europe decreased by 6.6 per cent between 2016 and 2018, but prisons in individual countries are still overcrowded, such as in Italy and France. This shows that many legal systems around the world still aren’t efficient enough, which is why authorities are increasingly turning to artificial intelligence for help.

AI-powered software used in the legal field comes in various forms. Some AI systems estimate the likelihood of a person repeating a crime and help judges in setting or denying bail, while others decide on small claims court disputes. Lawyers also benefit from AI, as it helps them to efficiently serve more clients. Smart chatbots even help people draft legal documents for free to eliminate hefty fees to legal professionals. But despite these efficiencies, the use of AI has a dark side as well, and it remains a divisive topic.

Biased big data leads to biased decisions

Take, for example, criminal risk assessment algorithms that predict the likelihood of a person reoffending. Such software is fed with historical crime data that might show that poor people or those living in particular neighborhoods are more prone to crime. Although correlation isn’t the same as causation, the high risk score might push the judge to deny bail and leave the person in jail until the trial. This can have devastating consequences, with people losing their jobs and homes, or even turning to crime to earn money, further reinforcing the existing bias.

What’s more, we don’t even know how risk assessment algorithms function. Back in 2013, in Wisconsin, Eric Loomis was sentenced to six years in prison based on, among other things, the algorithmic prediction that he might commit more crimes. His request to inspect or challenge the algorithm developed by the tech firm Equivant (formerly Northpointe) was refused on the grounds that it might reveal a trade secret. But even if judges in this case didn’t follow the recommendation made by the algorithm, it raised a whole new set of concerns. Dory Reiling, a former senior judge at the Amsterdam District Court, explains that “if judges do not perform according to the expectations raised by the artificial intelligence that will be a legitimacy problem for the court”. In other words, people will wonder why AI and judges differ so drastically in their assessments.

But for all its imperfections, artificial intelligence offers many benefits. Unlike judges, its decisions won’t be affected by presidential elections, football matches, or weather conditions. Also, machine learning policy simulation shows that smart algorithms could “cut crime up to 24.8 percent with no change in jailing rates, or reduce jail populations by up to 42 percent with no increase in crime rates”. And by predicting criminal behavior, the legal system can allocate resources more efficiently and reduce court backlog.

Can AI reduce court backlog and speed up trials?

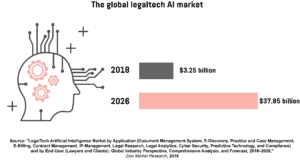

Artificial intelligence is used by various stakeholders in the legal industry. Lawyers use it to conduct time-consuming research and review documents, relieving junior staff of these tedious tasks, tech firms build algorithms that predict criminal trial outcomes, while software solutions used in courtrooms provide judges with easy access to a database of previous legal cases. And although crime risk assessment algorithms remain the most well-known application of AI in the justice system, the global legaltech AI market is clearly much bigger than that. In fact, it’s set to grow to $37.85 billion by 2026, driven by demand from both the public and private sector.

The Estonian Ministry of Justice, for instance, is one of the institutions that recognised the potential of AI in reducing court backlog. The ministry has instructed Ott Velsberg, the country’s 28-year-old chief data officer, to develop software which could solve small claims court disputes. The idea is that two parties upload documents and other relevant information, after which an AI would analyse the content and issue a decision. And if the parties are unhappy with the ruling made by the ‘robot judge’, they can appeal to a human judge. Velsberg hopes that the first pilot program could be launched in 2019, focusing on contract disputes, although he admits that the software might be adjusted once judges and lawyers send their feedback.

Meanwhile, a court in Shanghai took a different approach to AI. The Shanghai No. 2 Intermediate People’s Court uses software called the 206 System that follows voice commands and displays relevant information on digital screens in a courtroom. It also transcribes court proceedings and provides judges with access to case files and trial records. “At the trial, it can assist the judge to ascertain facts, identify evidence, protect the rights to sue and to a fair ruling, and ensure that the guilty are punished justly and the innocent not subject to criminal investigation,” says Guo Weiqing, the president of the Shanghai court.

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) Public Prosecution is also planning to use AI in the country’s legal system. Although details on these plans are scarce, the Attorney-General Dr Hamad Al Shamsi and the Minister of State for artificial intelligence Omar Al Olama recently intensified their cooperation in this matter by agreeing to train staff on how to use the latest technologies in the legal field. Also, the country boasts new digital courtrooms that enable witnesses, lawyers, or plaintiffs from anywhere in the world to participate in a hearing.

AI helps people save money on legal fees

Citizens and companies will be particularly thrilled by the fact that robot lawyers can save them a lot of money. The Robot Lawyer LISA (Legal Intelligence Support Assistant), for instance, is a software tool that enables people to write certain legal documents by themselves. Lawyers in the UK usually charge anywhere between $2,600 and $13,000 for a commercial lease document, while using LISA can reduce costs by up to 90 per cent. The program can also help users draft legally binding non-disclosure agreements, residential leases, and lodger agreements used by estate agents, management firms, landlords, surveyors, investors, and other companies.

The Dutch tech company SemLab has developed equally impressive software called JuriBot. This tool uses natural language processing, computational linguistics, and AI technologies to understand and structure data contained in court documents. For example, it can show the characteristics of the defendants or perpetrators, reveal specific parts of the documents, filter cases by lawyers or judges, and show acquittals and convictions data. It’s especially useful to trial lawyers and can “estimate which lawyer, at which court, for which type of offence, is most likely to achieve an acquittal”. The system is currently in beta testing, and the company plans to expand the scope of their product beyond criminal law.

A chatbot instructs users how to “sue anyone”

And if you’re unhappy with an unfair parking ticket, high bank fees, or late package deliveries, a free AI chatbot named DoNotPay will help you “sue anyone by pressing a button”. It generates formal letters that people can print, sign, and send to courts to become a plaintiff. DoNotPay was created by Joshua Browder, who claims that his software helped to appeal around 375,000 parking tickets in just two years. The service enables users to sue for hundreds of legal issues and is used in the UK and all 50 US states. Although Browder doesn’t currently earn anything from his app, he says that he might charge for “more specialized legal advice in the future”.

Much like Browder, the law firm Norton Rose Fulbright from Australia also uses an AI chatbot named Parker to help people save money. Lawyers tend to bill customers for answering even basic questions such as “How do I deal with a data breach?”. However, thanks to Parker, clients can now first talk with the chatbot and receive information that will help them decide whether they need legal assistance at all. And in case they do, they’re directed to three fixed-price legal advice packages. In its first 24 hours, Parker sold an impressive $10,700 worth of legal services.

The way Norton Rose Fulbright uses the chatbot illustrates why AI is increasingly popular in law firms. It saves time by providing basic information to clients and navigating them to the right attorney. Also, chatbots can automate sales and help lawyers learn which legal topics people are most interested in. Such insights can be used to create valuable content on the firm’s website and attract even more leads.

Defining our approach to the automation of justice

An irrelevant ad on Facebook’s newsfeed or lack of interesting movies to watch on Netflix may be seen as a harmless failure of smart algorithms. But sending an innocent person to jail and ruining someone’s life isn’t something that AI should be allowed to do. Sure, cutting-edge technologies may help us create a more efficient legal system, but we must approach this issue with the seriousness it deserves, as simply “Expediting the mass processing of people using AI isn’t the answer. It’s the opposite of justice”, says Song Richardson, the dean of the University of California-Irvine School of Law.

Predictive justice requires that algorithms adhere to key principles such as respect of human rights and non-discrimination. AI tools should be accessible and understandable, and subject to external audits. And to ensure that everyone gets a fair trial, both lawyers and judges need to be trained on how to use the new technology. After all, today’s legal challenges are just a glimpse of the future in which artificial intelligence is set to permeate all facets of our lives. Defining our approach to this technology will benefit both current and future generations.

Share via: