- Cheap renewable hydrogen is coming

- Europe is betting on hydrogen

- Germany unveils the world’s first hydrogen-powered train

- NASA plans to build an all-electric aircraft powered by cryogenic liquid hydrogen

- Toyota Mirai could be the hydrogen-powered car we’ve been waiting for

- Could hydrogen be the fuel of the future?

As the world becomes increasingly aware of the consequences of climate change, the pressure is mounting on companies across industries to find a way to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions before it’s too late. The transportation sector is one of the world’s biggest polluters, responsible for 14 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. Recognising the need to reduce its environmental impact, the sector has been working hard to improve the fuel efficiency of new cars and cut their harmful emissions. It’s also invested heavily in technologies that would enable it to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels, with electric vehicles proving increasingly popular among consumers. Even though they still hold a relatively small share of the market, electric vehicles are starting to gain traction, and there isn’t a single major car manufacturer out there that doesn’t have at least one of these vehicles in its lineup.

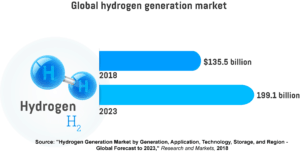

While most of the attention has been focused on electric cars, that’s not the only way for the transportation sector to reduce its environmental impact. Hydrogen gas has long been touted as the fuel of the future, a low-carbon alternative to fossil fuels that could help nudge the sector on the path towards zero emissions. While it never matched these lofty predictions, the production of hydrogen has increased steadily over the years, and this trend is expected to continue in the future. According to a recent report published by Research and Markets, the global hydrogen generation market is predicted to grow from $135.5 billion in 2018 to $199.1 billion by 2023. There are currently four ways to produce hydrogen: steam methane reformation (SMR), oxidation, gasification, and electrolysis. However, only one of these, electrolysis, has the potential to produce hydrogen without emitting CO2, while the remaining three rely on fossil fuels. Unfortunately, electrolysers required to complete this process have been prohibitively expensive, which is why electrolysis accounts for just 4 per cent of global hydrogen production. That may be about to change, though.

Cheap renewable hydrogen is coming

Researchers from several German universities, in collaboration with their colleagues from Stanford University, recently built a theoretical model of a wind farm connected to a hydrogen electrolyser to find out whether such a system could be profitable. In a paper published in the Nature Energy journal, the researchers describe a model normalised to a one-kilowatt system and paired with a polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolyser, which would allow investors to either sell all the electricity generated by the system back to the grid or use it to power the PEM electrolyser and sell the hydrogen it produces instead.

Based on the historical prices of electricity, the researchers determined that the price of hydrogen would have to be $3.59 per kilogram for the system to break even. However, even then it wouldn’t be able to compete with large-scale production of hydrogen synthesised from fossil fuels, which currently sells for $1.66 – $2.77 per kilogram, which accounts for the lack of renewable hydrogen systems at this stage. Things are starting to change, though. Thanks to the falling prices of wind turbines and electrolysers, the price of renewable hydrogen systems also fell by nearly 5 per cent in the period between 2003 and 2016, according to the researchers.

If this trend continues at the same rate in the future, the prices of renewable hydrogen are expected to become competitive with those of large-scale industrial hydrogen within a decade. With a little help from the government in the form of incentives for renewable hydrogen, this goal could potentially be achieved in half the time. However, lower prices alone won’t be enough to launch the renewable hydrogen revolution. We will also need to find a way to address the storage issue, build more refueling stations, and increase the number of vehicles powered by hydrogen fuel cells.

Europe is betting on hydrogen

Ørsted, the biggest energy company in Denmark, recently announced plans to convert some of its excess power into hydrogen gas. According to the company, electricity generated by wind turbines in the North Sea will be used to power on-shore electrolysis plants that split water into oxygen and clean hydrogen. In addition to providing another clean source of energy for vehicles and industries, this will also help take some strain off of Europe’s power grid by allowing it to store excess power in the form of hydrogen gas and use it to cover periods of weak winds and low solar output.

While many US experts have dismissed the idea of converting power into gas as being too expensive, Europe has recognised it as the best way to reduce the energy sector’s environmental impact. “In order to reach the targets for climate protection, we need even more renewable energy. Green hydrogen is perceived as one of the most promising ways to make the energy transition happen,” says Armin Schnettler, the head of energy and electronics research at the Munich-based electric equipment giant Siemens. There are currently more than 45 demonstration projects across Europe that aim to improve power-to-gas technologies and their integration with power grids and gas networks. Most of these projects have focused on finding a way to improve the efficiency and durability of electrolysers and reduce their costs. Siemens, for example, is working on technology that will be able to convert 10 megawatts, producing enough hydrogen each year to heat around 3,000 homes or fuel 100 buses.

Germany unveils the world’s first hydrogen-powered train

The European railway manufacturer Alstom recently announced the launch of the world’s first hydrogen fuel cell train called Coradia iLint. Two of the new trains will be put into service for the first time in Lower Saxony in Germany, where they will convey passengers along a 100-kilometre-long stretch of track that passes through the northern cities of Cuxhaven, Bremerhaven, Bremervörde, and Buxtehude. They will have a top speed of 140 kilometres per hour and will be able to cover up to 1,000 kilometres on a single tank of hydrogen, which is comparable to the range of diesel trains. Any excess energy will be stored in ion lithium batteries on board the train. The trains will refuel from a steel container installed at the train station in Bremervörde, while the company also revealed plans to build a stationary filling station to support future expansion of the fleet.

“The world’s first hydrogen fuel cell train is entering passenger service and is ready for serial production,” says Henri Poupart-Lafarge, Alstom’s chairman and chief executive officer. “The Coradia iLint heralds a new era in emission-free rail transport.” Unlike battery-powered vehicles, those that run on hydrogen fuel cells don’t require overnight charging and can be refueled just as fast as vehicles powered by fossil fuels. They’re also much quieter than diesel locomotives because they’re propelled by electric motors. The zero-emissions trains will replace their diesel-powered counterparts, and if everything goes as planned, the company will add 14 more hydrogen-powered trains to its fleet before 2021. After Germany, several other countries have also expressed interest in obtaining the trains, including the UK, the Netherlands, Italy, Denmark, Norway, and Canada.

NASA plans to build an all-electric aircraft powered by cryogenic liquid hydrogen

The aviation industry is also working hard to reduce its dependence on fossil fuels. A team of researchers from the University of Illinois recently announced they’re leading a new NASA-funded project called the Center for Cryogenic High-Efficiency Electrical Technologies for Aircraft (CHEETA), which will aim to develop a fully electric aircraft powered by cryogenic liquid hydrogen.

While hydrogen fuel cells have been touted as the future of transportation for quite some time, the technology currently at our disposal doesn’t enable us to build fuel cells with enough energy density to power a jet without weighing it down considerably. NASA wants to change that, and it’s provided researchers with $6 million to find a solution to this problem. To reduce the large volume requirement and increase the energy density of hydrogen fuel cells, the researchers decided to cryogenically cool the hydrogen and store it in liquid form. Since this type of hydrogen system would also require extremely low temperatures, the cryogen could also double as a heat sink to enable superconducting energy transmission and high-power motor systems, significantly increasing overall efficiency, specific power, and rated power capabilities of electric aircraft propulsion.

“The primary goals of the current program are to perform early development of technologies that could be used for the envisioned aircraft platform. While conceptual vehicles that feature electrified propulsion systems are in no shortage these days, the actual electrical motor, power electronics, system management, and propulsion integration practices required do not yet exist to make these vehicles a reality. Our team seeks to address this gap by advancing the capabilities of key enabling technologies for large electrified commercial aircraft of the future,” says Phillip Ansell, the principal investigator for the project and an assistant professor in the Department of Aerospace Engineering.

Toyota Mirai could be the hydrogen-powered car we’ve been waiting for

While most of the world’s car manufacturers are going all in on electric vehicles in an attempt to reduce the sector’s greenhouse gas emissions, the Japanese automotive giant Toyota is taking a slightly different approach. The company recently unveiled a new version of its hydrogen-powered vehicle called Mirai, which features an improved design, better driving performance, and significantly longer range. The five-seat, rear-wheel drive Mirai is built on the same modular vehicle platform as the luxury-class Lexus LS flagship sedan and is expected to go on sale in 2020 in Japan, North America, and Europe.

Toyota hasn’t revealed many technical details at this time, but the new version is expected to exceed the earlier model’s 152bhp and 335Nm of torque. The new version will also be equipped with an upgraded fuel cell stack that will be able to store more hydrogen, extending the vehicle’s range by 30 per cent to just over 700 kilometres, which will be difficult to match for any electric car out there. According to Shigeki Terashi, Toyota’s executive vice-president and chief technology officer, the company also plans to offer the technology to its global partners for use in buses, trucks, and other mobility devices.

Could hydrogen be the fuel of the future?

Once hailed as the fuel of the future, hydrogen never managed to live up to its promise, and the transportation sector gradually shifted its attention towards other solutions in an effort to reduce its environmental impact. However, thanks to recent technological advancements, hydrogen is once again back in the spotlight as a potential alternative to fossil fuels, and it seems to be the real deal this time.

With Germany rolling out the world’s first hydrogen-powered trains, NASA working on an all-electric aircraft powered by cryogenic liquid hydrogen, and some of the world’s largest car manufacturers embracing this fuel source, hydrogen-powered vehicles could soon become a common sight. Only time will tell whether hydrogen truly is the fuel of the future, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction and could pave the way for the decarbonisation of the transportation sector.

Share via: