- AI can now turn what the brain sees into a reconstructed image

- Redefining how a deep neural network ‘sees’

- The AI system’s accuracy is astonishing and slightly creepy

- Privacy advocates voice their concerns

We recently wrote about mind-reading tech that allows words you merely think to be transcribed into speech. That’s an exciting development, and since this amazing brain-computer interface (BCI) comes in the form of a non-invasive wearable, it’s possibilities are staggering. From helping people who’ve lost motor control to speak or control their home appliances, to assisting workers in dangerous, noisy environments, this new tech has a bright future.

But research into BCIs hasn’t stopped there, and our ability to decipher the workings of the mind is growing rapidly. One promising approach uses fMRIs, a special form of magnetic resonance imaging that detects blood flow in the brain, to reconstruct an image the subject sees or remembers. Using very smart algorithms, these artificially intelligent systems can translate brain activity into images with startling accuracy. And while this tech lacks real-world applications at the moment, it’s refining how we understand the mind. Make no mistake – that’s a big deal. As Catherine Clifford observes, advanced versions of this tech could soon lead to wearables that allow artists to paint with their minds, psychotic patients to receive more effective treatment, or even ‘telepathic’ communication systems.

AI can now turn what the brain sees into a reconstructed image

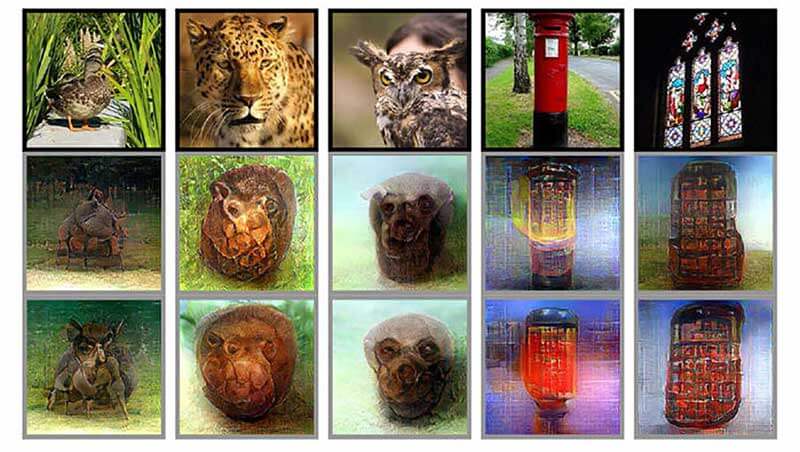

A team of researchers from Kyoto university led by Guohua Shen, includiung Tomoyasu Horikawa, Kei Majima and Yukiyasu Kamitani, has been working on a system to interpret what the brain sees and represent that information as a reconstructed image. Essentially, they’re looking at brain activity with an fMRI, and re-creating what the eyes are seeing using a deep neural network (DNN), a form of artificial intelligence (AI) that mimics how the mind works.

The challenge has been that, without first training the DNN on millions of pre-selected images, no one thought the algorithms would have enough information to reconstruct what a test subject is seeing. As the authors write, “direct training of a DNN with fMRI data is often avoided because the size of available data is thought to be insufficient to train a complex network with numerous parameters.” This team, however, managed an ‘end-to-end’ solution, enabling the DNN to read brain activity and reproduce images with only 6,000 sample images.

As Tristan Greene reports for The Next Web, “Basically the old way was like showing someone a bunch of pictures and then asking them to interpret an inkblot as one of them. Now, the researchers are just using the inkblots and the computers have to try and guess what they represent.” And in practice, this now means that it’s feasible to teach a DNN to interpret fMRI data without access to a massive library of images, simplifying the process and making it feasible for real use.

Redefining how a deep neural network ‘sees’

Another breakthrough for imaging thoughts was this team’s new approach to how these image reproducing DNNs go about their work. Instead of focusing on pixels, Shen’s team modelled how our own brains interpret what we see, using hierarchy to make out what was important. “Our previous method was to assume that an image consists of pixels or simple shapes,” Kamitani explains. “But it’s known that our brain processes visual information hierarchically extracting different levels of features or components of different complexities.” And as Clifford reports for CNBC, that means that “the new AI research allows computers to detect objects, not just binary pixels.” In other words, the team’s DNN can distinguish an object, not just ‘see’ a pattern of shapes. And as Kamitani notes, “Unlike previous methods, we were able to reconstruct visual imagery a person produced by just thinking of some remembered images.” That’s pretty amazing, right?

The AI system’s accuracy is astonishing and slightly creepy

Shen’s team is far from alone, and research teams everywhere are hard at work. For instance, psychologists from the University of Toronto used a similar system that collects its data from an electroencephalogram (EEG), basically a measure of the electrical activity of the brain, to recreate the faces test subjects were viewing. James Felton, a reporter for IFLScience, describes the accuracy of this AI system as “astonishing and slightly creepy”.

And advances continue at break-neck speed. For instance, as Adam Jezard writes for the World Economic Forum, “scientists at Carnegie Mellon University in the US claim to have gone a step closer to real mind reading by using algorithms to decode brain signals that identify deeper thoughts such as ‘the young author spoke to the editor’ and ‘the flood damaged the hospital’. The technology, the researchers say, is able to understand complex events, expressed as sentences, and semantic features, such as people, places and actions, to predict what types of thoughts are being contemplated.” That’s pretty close to reading minds in real life, for better or worse.

Privacy advocates voice their concerns

Indeed, there’s no question that that’s a huge advance, but it has privacy advocates concerned. Unlike the speech tech we talked about before, this has potentially disturbing implications. As Tristan Greene worries, as it becomes more sophisticated, “this technology could be used by government agencies to circumvent a person’s rights. In the US, this means a person’s right not to be ‘compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself’ may no longer apply.” And Adrian Nestor, one of the researchers at the University of Toronto, thinks that their facial image reconstruction tech “could also have forensic uses for law enforcement in gathering eyewitness information on potential suspects rather than relying on verbal descriptions provided to a sketch artist”.

That’s a frightening possibility, even when used for good. As Jezard notes, “researchers and governments have yet to spell out how they can ensure these [technologies] are used to benefit the human race rather than harm it.”

That sounds like a good place to start, and as excited as we are by this tech, some careful forethought can’t hurt.

Share via: